The first car in the world and its inventor

|

| The first car in the world and its inventor |

|

| The first car in the world and its inventor |

People have had information of the wheel for a few thousand years, and we've been utilizing creatures as a wellspring of transportation for about that long. Thus, in some sense, the most punctual trailblazers of the auto go back to the soonest fogs of our ancient times. In any case, maybe a more helpful state of mind of the auto is anything that could sensibly be called a "car" - as such, any vehicle fit for driving itself. All things considered, we're at most discussing 439 years of auto history.

|

| The first car in the world and its inventor |

|

| The first car in the world and its inventor |

The Emperor's Toy

The main auto may well have been the creation of a Flemish minister named Ferdinand Verbiest. Conceived in Flanders in 1623, Verbiest was a refined stargazer who left Europe for China in 1658. He modernized the now outdated Chinese cosmology utilizing late European advancements, and he was requested that by the ruler turn into the executive of the recently renovated Beijing Ancient Observatory. Besides, talked no less than five dialects fluidly, composed thirty books, was a gifted negotiator and mapmaker, and mentored the enduring Kangxi Emperor in everything from arithmetic to verse. He was, even by the measures of the time, strangely expert.

Mistake stacking media: File couldn't be played

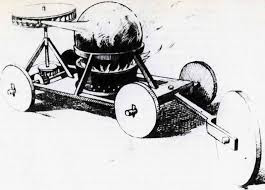

In any case, the motivation behind why we're discussing Verbiest here is that he may - accentuation on might - have designed the world's first auto. As per Verbiest's own particular content Astronomia Europea, he manufactured a little, self-impelled vehicle. Steam innovation was still in its early stages at the time, yet Verbiest could manufacture a simple, ball-formed heater, which then constrained steam towards a turbine that could turn the back wheels. Verbiest says the vehicle was intended to be a toy for the ruler.

Considering this is more than 200 years before the development of what's by and large considered the main present day vehicle, this is a surprising accomplishment, yet there are some quite enormous provisos here. I said the auto was little, and it was: around two feet long, very small for any human to ride in it. It's additionally not in the least clear whether the toy was ever fabricated, or on the off chance that it absolutely existed as an outline in Verbiest's creative energy.

We do know Verbiest's cozy association with the head gave him access to the finest metalworkers China brought to the table, so it's not inconceivable that he manufactured the toy. What we can state is this - Verbiest in all likelihood composed what was successfully one of the most punctual scale models of a car. (In spite of the fact that, in case we're simply discussing outlines for autos, then Leonardo da Vinci has Verbiest beat by a decent two hundred years. In any case, Leonardo unquestionably didn't assemble his, so Verbiest has that on him.)

The First Engine

To some degree, 1672 may appear to be shockingly later for the main auto ever. All things considered, we continue finding significantly more antiquated analogs for present day things, including everything from Babylonian historical centers to Roman fishtanks. So why haven't we found an antiquated Egyptian auto inside the pyramids, or even some medieval gadgetry that ambiguously approximates a car?

The story behind the world's most established historical center, worked by a Babylonian princess 2,500 years back

In 1925, prehistorian Leonard Woolley found an inquisitive accumulation of antiquities while…

Perused more on io9.com

Part of the motivation behind why it took until 1672 for anybody to try and fabricate a toy form of an auto was that there was quite recently no requirement for them, and it wasn't generally the kind of thing one could develop in a single killer blow. In World History of the Automobile, Erik Eckermann clarifies the fundamental issue:

The wagon existed in its creature drawn frame for a great many years before it was conceivable to make it self-pushed, truly "auto-portable." all the while, mechanized vehicles were far expelled from the focal point of logical and mechanical request. From the finish of the seventeenth century, existing vehicular innovation was more than sufficient to meet societal requests. In the period of total rulers and mercantilism, it was more vital to unravel other building challenges that were troublesome or difficult to accomplish with ordinary vitality sources, for example, muscle, wind, or water control.

What's more, what were these more essential designing difficulties? As Eckermann clarifies, "the wellsprings and water showcases of ornate greenery enclosures" were a higher need for innovators and researchers than was the formation of a self-impelling vehicle. While nobody was truly handling this subject specifically, the incredible Dutch researcher Christian Huygens took a vital stride towards the auto in 1673, one year after Verbiest supposedly started take a shot at his toy for the sovereign of China.

Huygens based upon past analyses by different researchers to make a basic motor controlled by, marvelously enough, black powder. By detonating the material inside a chamber, Huygens could make a vacuum, which thus constrained a cylinder to move down the barrel. This made work, making it successfully the most punctual conspicuous precursor of the inner burning motor. What's more, as far as concerns him, Huygens instantly perceived the motor's potential as a power hotspot for land and water vehicles alike, yet his motor was awfully primitive to be of much use in that heading.

Cugnot's Car

The 1700s were commanded by different creators attempting to culminate the steam motor - Thomas Newcomen and James Watt are presumably the most celebrated of these, however there were some more. Be that as it may, the primary individual to take a steam motor and place it on a full-sized vehicle was presumably a Frenchman named Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot, who in the vicinity of 1769 and 1771 fabricated a steam-controlled car over thirty years before the railroad's first steam train.

Cugnot's plan was, to understate the obvious, extraordinary. The contraption weighed around 2.5 tons, had two major wheels in the back and a solitary thick focal wheel at the front, and could situate four individuals. The heater was put well out in the front, which made the vehicle much more wickedly hard to control. While its top speed was intended to be around five miles for every hour, it never at any point drew near to that quick practically speaking.

Supposition is to some degree separated over how well the thing really functioned - in reasonableness, different government priests should be inspired with the underlying trials - albeit most concur that it had poor weight conveyance as was not able handle even respectably unpleasant landscape. Since its planned reason for existing was as a vehicle for overwhelming mounted guns on the war zone, that must be viewed as a disadvantage.

One story says that the second of Cugnot's two vehicles collided with a divider in 1771, which may make it the main ever car crash. It's a decent story, however lamentably nobody expounded on it until 1801, approximately thirty years after the fact, which makes it rather more probable this was a tad of old stories. In any case, here's a fairly great remaking of the crash, totally with absurdly over-the-top response shots.

The Steam Busses

As France fell into the grasps of insurgency, Cugnot's work was to a great extent overlooked, and the following huge developments in vehicle innovation came in Britain. Throughout the following quite a few years, different innovators dealt with steam carriages, which looked like a combination of transports and rail trains. William Murdoch made a working model of one of these in 1784, however it wouldn't be until the start of the nineteenth century that Richard Trevithick could get a full-sized vehicle out and about.

Steam-controlled mass travel had some restricted achievement in the opening years of the 1800s, however it wasn't until the 1830s that steam transports started increasing some measure of ubiquity with the British open. Encourage mechanical developments in this early type of street based mass travel including better brakes, a more propelled transmission, and enhanced directing.

Be that as it may, as Erik Eckermann clarifies, the disadvantages still far exceeded the benefits of this new innovation:

It was clear that the innovation was not yet completely created, and this new method for transportation did not yet appreciate great popular sentiment. Crankshafts snapped, lines spilled, chains broke, and boilers detonated. Motor vibrations (which, not at all like stationary establishments, couldn't be overcome by mounting on a strong establishment, the sharp scent of smoldered oil, and flying residue and coal tidy soon drove the venturing out open back to the old standby, the steed drawn stage, or another new development, the railroad and its quickly developing system of track.

The steam transports ended up being something of a deadlock, and architects turned their consideration regarding footing motors, which were slower, more steady machines that were fundamentally simply steam trains adjusted for use ashore. This was a move far from the line of development that would in the end prompt to the auto, yet even these demonstrated excessively boisterous for the general population on the loose. The Locomotive Act of 1865 said no land vehicle could travel quicker than 4 miles for every hour, and that every such vehicle must be gone before by a man waving a warning and blowing a horn. This was not, as you may envision, the car business' finest hour.

Different Curiosities

There were a few different endeavors to construct self-impelled vehicles, yet none of them ever very made that enormous jump to end up distinctly the primary down to earth car. An American designer named Oliver Evans constructed the "Oruktor Amphibolis", a steam-controlled digging gadget that turned out to be all the more effective and expand with each consequent retelling, to some extent since Evans felt he never got legitimate credit for his building ability. Now, it's hard to state with assurance precisely what the Oruktor Amphibolis was really able to do.

Russian innovator Ivan Kulibin cam

0 comments:

Post a Comment